Ethel Leontine Gabain was born on March 26th 1883 in Le Havre France. As a child she began to spend her time sketching and painting the surrounding headland and strolling down to the harbour to make pencil drawings.

Most of her first twenty years were spent in France and according to her mother, Bessie Gabain, it was a very happy and interesting life she had with her brother William, and four sisters, Dorothy, Marjorie, Ruth and Laura. There were Sunday afternoon walks along the cliffs, stories told by their father which continued from week to week, the garden with fruit trees, trapeze, swing and seesaw. Much bathing took place in the warm summer sunshine and there were many trips by boat across the bay to Trouville. When they were a little older there were bicycle rides in beautiful Normandy to Tancarville and Caudebec all delightfully captured by Ethel in small pencil drawings.

Ethel was half French and half Scots. Her father, Charles Edward Gabain was a well off French coffee importer who spent some considerable time away from home in Brazil. When he had made his money he decided to retire, move the family to England, and start a new life in Hertfordshire, where he bought an attractive large house in Bushey, named the Manor House.

Ethel decided she would earn her living as an artist. She entered Collins Studio, Paris and became an associate of the Salon des Artistes Français early on in her artistic career.

At the age of twenty-three she decided to leave France and move to England for a time. She knew England reasonably well and spoke fluent English having boarded at Wycombe Abbey School, Buckinghamshire from the age of fourteen. At Wycombe Abbey she was encouraged as an artist. Later the school commissioned her to paint Miss Ann Watt Whitelaw, headmistress from 1911 to 1925.

Ethel was accepted by two prominent London Schools, the Slade School of Art, and the Central School of Arts & Crafts, Regent Street. The place to study lithography, her chosen medium, was the Central School of Arts & Crafts, with its director of lithography the artist, F. E. Jackson, who had access to a fully equipped studio, housing 60 lithographic stones. By 1908 his classes attracted a good number of artists who went on to become excellent lithographers including Ethel Gabain.

She was also determined to do all her own printing. The lithographic press was huge, dirty and heavy, and it needed a lot of skill to use it. Most of all it took a lot of strength to turn the handle to produce a print. Undaunted she attended lithography classes at the Chelsea Polytechnic and learnt how to work a printing press. Later when she had become a proficient printer she said:

It really is advisable for the artist to print their own proofs, if possible, since if they do not understand all about printing and have not had considerable practical experience in it, they will not obtain the best effects in their prints. No matter how experienced one may be at printing the first proof invariably looks different in tone from the drawing on the stone and it always gives a degree of concern. The previous somehow more greyish appearance of the lithographic chalk drawing on the stone surface is now replaced by the luminous rich black of the printer’s ink on the print, and this sudden access of tone has to be reckoned for. There is only one way for the artist to ensure the desired delicacy or strength or contrast of tones in the print itself is to … do it yourself.

Her first lithograph, Sewing was a copy of a Japanese print and purely experimental. It was in colour using six stones. Still experimenting she produced another coloured lithograph, a copy of the portrait of Edward VI, in the National Portrait Gallery — this time she used only three stones. These experiments helped her realise that colour was not what she wanted; she sought to produce brilliant rich black and white lithographs. Her work was now on show in France and England: at the Salon des Artistes Français, Paris and the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, where she had three lithographs on show: The Muff £1:1:0, Scaffolding University College, London £1:10:6 and Miss K £2:2:0. Two years later she exhibited her first portrait at the Royal Academy, Princess Christian of Denmark after Holbein. Her portraits were becoming more well known and she began to receive commissions. Her address at this time was St. Andrew’s House, Mortimer Street, West London, and she produced a lithograph of her studio named: The Studio Stove.

In 1909 Ethel exhibited two more lithographs at the Royal Academy, The Virgin of the Column and The Black Bow and her address was now 17 Rue Boissonade, in the 14thArrondissement of Paris. Having taken a small studio there she attended classes to obtain practice in drawing from the model. She also went and served an apprenticeship with an experienced lithographic printer, who let her produce her own lithograph, The Virgin of the Column, Musee de Cluny, which she had drawn direct on the stone in the courtyard at the museum.

Before leaving England to study in Paris she contacted a well know London print seller with a view to publishing some of her lithographs. He told her there was no demand for lithographs in England, but since she was returning to Paris where they were popular, he would give her the name of a Parisian print seller who might be interested in her prints. She presented her introduction and he immediately purchased a number of them remarking upon their quality and originality.

Whilst living and working in the Rue Boissonade Ethel produced Mother and Child, The Mother and L’Enfant Endormi. The last was produced after a visit to Concarneau. Seeking new material she decided to leave Paris to work in Italy for a time, staying in and around Florence and returning to England via Switzerland. All her work was done on transfer paper then transferred from the paper to the stone at her London studio in Brook Green.

On her return to England Ethel was invited by a number of well known lithographers to form a club with them, their intention was to introduce lithography as an art form to the English Art Scene. The Senefelder Club, named after the inventor of lithography, was founded by Ernest Jackson, A.S. Hartrick, Joseph Pennell and J. Kerr-Lawson. They invited J. McLure Hamilton, John Copley, Miss A. E. Hope, Harry Becker and Miss Ethel Gabain to join. Joseph Pennell was the Club’s president and John Copley, her future husband, its secretary. The Club’s aim was to make lithography as widely accepted as etching in the public’s eyes. The market for etchings was strong; it was accepted as a fine art and taught in art academies. They wanted lithography to be seen as an art not just a trade.

The club’s first exhibition was held at Mr. William Marchant’s Goupil Gallery in London in January 1910. Ethel contributed six lithographs: Madame Jeanne, The Mother, Mother and Child, Tired, Coin de l’Atelier and The Virgin of the Column. In 1912 as a member of the club, she exhibited at the Salon de l’Estampe Brussels, The Pulchri Studio, The Hague, of which she later became an honorary member, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts; and the International Exhibition, Venice. The group also had special shows in the City Art Galleries of Bradford and Liverpool, and exhibitions of proofs at Toronto, Bombay, Simla and Melbourne.

About this time Harold J. L. Wright of P. & D. Colnaghi saw her print The Striped Petticoat of 1911, and he immediately contacted Ethel to ask her if the company could become her publishers. In 1913 she and John Copley married and shortly after they moved to The Yews, at Longfield in Kent. Whilst they lived there Ethel adopted a small remarque in the shape of a yew tree in the lower margin of some of her prints, indicating that she had printed it at Longfield. The pergolas and the sundial in the garden at Longfield also appear in some of her lithographs.

Ethel and John worked together, exchanging ideas and sometimes sharing the same subject. But their lithographs always remained quite different. On the 20th May 1915 Ethel and John’s first son, Peter, was born. With a baby Ethel’s output slowed and she made only seven prints in that year. Her work reflected her motherhood and, perhaps feeling trapped by domesticity, she started a series of lithographs on the theme of Pierrot and Columbine.

Her work was receiving strong and encouraging comments in the press. Campbell Dodgson (Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum) wrote in Colnaghi’s 1920 Catalogue of Lithographs by John Copley and Ethel Gabain: ‘They are amongst the most accomplished of those who are practising the art of original lithography in England at the present time, and are raising its status in the estimation of the discriminating public. I doubt if any other lithographer of today can claim such virtuosity as Miss Gabain possesses in her command of all the range of colour that lies between blackest black and whitest white in the lithograph.’

Soon after she had completed her first poster, for London Transport, John’s work abruptly came to a standstill. He was diagnosed with a weak heart, an affliction which had struck him when a student. It meant he had to spend hours resting and was only allowed to draw for an hour a day. His doctor suggested he should convalesce, so they decided to take a cottage at Wye, Kent and whilst he recuperated Ethel began to work again sketching and painting the surrounding scenery, particularly the trees. When their stay was over in Wye and family life seemed back to normal Ethel started to work again on a project which took up the whole of 1922. Edmond Paix, a French collector and bibliophile, had seen The Striped Petticoat and commissioned a special edition (495 copies) of Jane Eyre from Monsieur Leon Piton of Paris. Paix

Hampstead Square

For a variety of reasons John and Ethel decided to leave their bungalow in Kent and moved to 10 Hampstead Square, NW3, an attractive large late Victorian house built in 1890.

I remember a wall was knocked down between the two downstairs rooms at number 10, making it one enormous room. My parents then partitioned it with a huge floor to ceiling curtain. I particularly remember it had a gorgeous William Morris design on it. In so doing one side became a workroom with the etching press, stored prints, lithographs etc., and the other side became the living room.

My parents seemed to have many dinner parties, but it was not until much later I realised the star studded names that sat around the table. Once my acting career took off Edith Evans (a close friend of the family) and Flora Robson, who lived at 37 Downshire Hill, were invited to dinner.

The Senefelder Club was now well established and Ethel was a prominent member. An article in the Times gave her work an excellent review:

The artistic possibilities of lithography, its freedom, directness, and responsiveness to every mood of the draughtsman, are well shown in the present exhibition of the Senefelder Club at the Twenty-One Gallery, Adelphi. What the method allows in range of tone can be seen in “The Summer Room,” by Miss Ethel Gabain, the light reflection in the dark framed mirror being a very effective crisis.

The Twenty-One Gallery was the headquarters of the Senefelder Club and in 1926 the club announced that the “Lay Member’s Print” issued to subscribers, would be by Miss Ethel Gabain.

The Warden

Ethel’s workload was steadily increasing. She now had her own studio on the top floor of this splendid Victorian house with a balcony overlooking the square. This balcony became part of her life and would appear in many of her future works. Once she and John had the etching press up and running she began to think about doing some more illustrative work. She wrote a letter from Hampstead Square on 26th January 1924 to John Lane, who was co-founder of the Bodley Head. In this letter she explained how she was anxious to do some illustrative work in England and would like to make an appointment to show him some of her current work as well as the illustrations she produced for Jane Eyre. Lane must have passed her letter on to his colleague B.W.Willett who contacted Ethel suggesting they meet on the 30thJanuary. The fruition of these letters was a commission for nine lithographs for The Warden (42) by Anthony Trollope, published by Elkin Mathews & Marrot Ltd., 1926.

Alassio, Italy

When this commission was finished Ethel had to make a decision which would affect the whole family. She was still very anxious about John’s health, and on his doctor’s advice to go and spend some time in a warmer climate, the family moved to Alassio, Italy. Described by Peter as a magical time:

I admired my mother so much. She organised the letting of the house and we went to live in Italy for two and a half years. I was 10 and Christopher was 7. We went out by Dutch boat setting out from Southampton. There was a great storm in the Bay of Biscay and my mother, Christopher and myself were very sea sick. We just lay there feeling awful. My mother was completely exhausted. My father who had been up on the deck was reborn and using his Italian name for her, Carina mia, he exclaimed “Carina mia it is wonderful out there. I am ashamed of you lying here.” My mother said if she had the strength she would have willingly hit him.

We were there from 1925–27. My mother’s energy and enthusiasm were unbelievable. We stayed in our hotel down by the sea and off she went to find us a home, which was not so easy since she had to deal with the local estate agents and she didn’t speak a word of Italian. She found us a small rented villa on the hillside with a beautiful view overlooking the Mediterranean. There were enough English people in Alassio to provide a church and school, and Christopher and I attended the school which two English ladies had started.

Typically of my mother, whilst we were in Alassio her conscience suddenly hit her. Although she was not a religious person and my father was not at all religious and did not go to church, she decided Christopher should be christened. I had been christened as a baby at the Manor House by the then Bishop of London, who by all accounts was a very pompous man indeed. My father was appalled at what was demanded of the god parents and said no further child of mine is ever going to be christened. Now Ethel had decided this was wrong and that Christopher should be christened by the nice vicar and then he was free to do what he wanted later on. Rather bizarrely, I was Christopher’s god father and I was due to join them at the church after I had been to school. I arrived three quarters of an hour late for the service much to my mother’s horror, I think I thought it was all a bit silly.

Whilst in Alassio mother spoke in French and learnt bits of Italian. Later on a very sweet girl from a nearby fishing village came to work in the villa – who in the end was speaking my mother’s Italian with French.

Father lived in the villa up on the hill and did not move much from there. He wore silk pyjamas in the warm climate and painted and drew on paper not stone, and my mother took art classes within this English colony to earn some money. It was a good and happy time in Italy.

Once back in England it was frightening to see how fast John’s health began to deteriorate, and Ethel was extremely concerned. He was very ill and had to lie still for hours on end. Ethel had all the familiar feelings of anxiety back again and wondered how she would cope. She was totally convinced John would never be able to work again. She reveals this in a letter sent to her good friend Elizabeth Pennell in October 1928. (Now in Harry Ransom Centre, The University of Texas.)

We so much enjoyed Mrs Crawford’s visit and were delighted at her suggestion to have an Exhibition of our prints this Autumn in the Philadelphia Print Club. It was nice to have news of you from her. The boys have grown past recognition. Peter a real man with a great gruff voice. He is a dear boy, a real friend to us both and has grown into a huge fellow taller than either of us. Christopher is doing well at school and he has at present decided to be an Astronomer!

Herbert (John’s real name) is wonderfully better now. He was terribly ill after we came home from Italy, in bed practically from June to March and as the Doctor said it was a miraculous recovery. Colnaghi’s are having an exhibition of our work in May so we are working hard for this. Hartrick comes often to see us, he doesn’t seem to change and I can’t imagine him ever being very young — and he is just the same dear old thing now as I remember him 20 years ago.

The exhibition referred to by Ethel in her letter took place at Messrs. Colnaghi and the Times’s critic wrote the following:

In the work of Miss Ethel Gabain and Mr. John Copley at the galleries of Messrs. Colnaghi. 144 New Bond Street. Miss Gabain’s is the slighter talent, in both matter and manner, her subjects ranging from Pierrot to Venetian scenes and types, and from incidents of the boudoir to landscapes.

Her designs are decorative in pattern rather than in movement, and if her work has a defect it is that it relies too much on the charm of subject matter – period costume and the appointments of graceful interiors.

It is to be observed that Miss Gabain has an admirable sense of the abstract appeal of space and proportion in architectural settings. Technically the work of both artists is excellent.

Oil Painting

The market for prints collapsed in 1929 and Ethel and John were struggling financially. Ethel realised she would have to turn to painting and began to work in watercolour and oil. Many of their colleagues had moved away from lithography much earlier. She sent her first oil flower painting, Zinnias to the Royal Academy in 1927. She began a series of paintings of young brides in the 1930s, always using the same model, Carmen Watson. Carmen had posed over 60 times for Ethel by 1940.

Theatrical Portraits

Ethel decided to help Peter with his chosen theatrical career, and she painted a number of famous actresses: Peggy Ashcroft in Romeo and Juliet, Diana Wynyard In The Silent Knight, Miss Flora Robson As Lady Audley, Edith Evans In Restoration Comedy, and the theatrical genius Lilian Baylis.

Peter said:

To my absolute horror she would approach certain famous actresses and offer to paint their portraits. She would ingratiate herself with leading actresses, saying Peter’s an actor now – as if seeking their help and pushing me as an actor. I was so embarrassed. She would invite them to dinner and somehow end up painting their portrait. She painted lots of famous portraits and I have to admit they were very good.

She did a painting of Peggy Ashcroft as Juliet and engineered it all herself. It was a season of Gielgud, Olivier and Peggy Ashcroft at the Albery Theatre, so my mother went along, sat in the stalls and photographed them, and the end product was an extremely good portrait of Peggy Ashcroft as Juliet. John Gielgud became a friend of the family.

Ethel won the 1933 De Laszo Silver Medalfor her portrait of Flora Robson as Lady Audley. Oldham Art Gallery purchased Adelaide Stanley – In The Two Bouquets for £75 and Edith Evans in Restoration Comedy by the Stoke-on-Trent Art Gallery in 1935.The Walker Art Gallery bought Diana Wynward in The Silent Knight in 1938.

–

Ethel tried to help both her sons with their careers. She wrote a passionate letter to The Times in 1939. Christopher was training to become a doctor, and as a parent she was concerned that his training had come to a standstill. She wrote: “These boys are to be the doctors of the future, and it is they who are to fill the gaps in the profession made by the war. May I add a plea from parents that some constructive plan should be devised to give them as good a training as they would have had before the war. Is the need for that not even greater now?” The British Medical Journal and The Lancet certainly agreed with her.

Both John and Ethel had been elected members of the Royal Society Of British Artists. In the late 1940s, when John was President of the Royal Society, he knocked on Vivien Leigh’s theatre dressing room door and asked her to open their annual exhibition. She did, and drew large crowds

Even though they were both working flat out, they were still struggling financially. Ethel decided she would go and lecture to a number of girls schools on the art history of whichever country was the subject of the current Royal Academy Winter exhibition. She started with her old school Wycombe Abbey and then built up a circuit.

My father wrote the lectures because he was an historian. Mother definitely was not. She could lecture very well, in fact with incredible flair, but when it came to question time she struggled to answer the questions and moved off very quickly. After a while she became so successful she was booked up months in advance

During this period Ethel’s health deteriorated, and she contracted a serious kidney illness which led to her having to have major operations in 1938, 1941 and 1943.

The operation took its toll. To add to her problems she was also suffering from arthritis which was getting worse and beginning to impede her work. On the 16th March 1940 Christopher, who was training to be a medical student, tragically died at the age of 21.

Soon after she decided to contact the Ministry of Information and offer her services as a War Artist. She explained how she thought it was essential, through her art, to let people know the important roles women were now playing within the war effort. She was accepted by the Ministry and once again she turned to making lithographs.

In the series Women’s Work in the War she depicted confident young women working on the land, flying planes, felling trees, mending tanks and planes and filling sand bags.

Masses of photographs were taken as source material, and whenever possible John would go with her. She worked throughout the war and when she finally became crippled with arthritis, and it was painful to hold her paint brush, she strapped it to her wrist and carried on.

No matter how hard she worked and how ill she became, my mother would not give in. After her operation in 1943 she carried on working. I admired her so much, but in a way it was quite upsetting because she would worry so about her appearance. She was frail and thin and to try and disguise this she wore extravagant hats and combed blacking through her hair, whitened her face with powder and wore very red lipstick. We were so upset, this fine lovely lady did not need to do this, but we could not stop her.

Ethel died on 30th January 1950. After her death John organised a memorial exhibition of her paintings and lithographs at the Royal Society of British Artists, Suffolk Street, London. In the foreword of the exhibition catalogue he wrote: “She could only paint when she saw something in front of her that she felt to be beautiful.”

Martin Hardie, Keeper of the Engraving Department at the Victoria and Albert Museum added:

Besides exhibiting constantly at the Academy she became a member of the R.B.A. in 1932 and from that date was a regular exhibitor in Suffolk Street. As a painter she approached her task with depth of feeling, with entire sincerity, and with humility of spirit. Seeing with her eyes or with inner vision the beauty given by some blending of form and line and colour, she concentrated every faculty, with complete honesty, to search out and reveal what underlay the beauty, and to interpret it clearly so that other eyes might share her pleasures.

On 17thJuly, only five months later, John died peacefully at Hampstead Square, London.

Ethel Gabain in the Second World War

During the war years Ethel produced a series of lithographs and oils both as a record and for propaganda purposes. Despite her deteriorating health she was determined to make a contribution. Women of all ages and in all walks of life found their lives transformed by the War. Thousands of women had seen their children evacuated from London and the South East not knowing when they might return.

Working Women

As the war continued more and more women were needed to take over men’s jobs as they joined the armed forces. In 1941 the government announced that unmarried women aged between 20 and 30 would be called up for war work. A year later, 19-year olds were also conscripted, and were offered a choice between the Auxiliary Services and jobs in industry.

Married women were not conscripted but they were under great pressure to volunteer for war work. Thousands of women with children needed to work for extra income because a serviceman’s income was so low.

Normal life no longer existed for working women, especially those with long factory shifts. They found shopping virtually impossible — shops now closed earlier to save power and everything was rationed and bought up with coupons before they could get near. Many women workers had to sort out their own childcare, usually depending on relatives and neighbours. The Ministry of Health did nothing to help until 1941, when it was forced to take some action and make sure all local educational authorities provided nurseries. At the end of 1940 there were 14 nurseries in the country, by 1944 there were 1,450.

Attitudes changed during the war, but at first women were made to feel guilty if they stayed at home and guilty if they went to work. Numerous advertisements appeared in women’s magazines encouraging women to manage their job but in so doing not to let standards slip at home. One typical advertisement asked Can A Warden Be A Good Wife?

For some working women the war brought them a greater degree of independence and meant they now had the opportunity to train for skilled jobs and higher earnings. Nannies, cooks and maids found their wages tripled. Many young women found freedom, companionship and financial independence.

Ethel was an extremely sensitive person: she could associate herself with these women and the way they individually handled this awful war. She was determined to capture their intimacy in her war-time depictions and she did in her own unique way.

The War Artists Advisory Committee

This Committee was created during the First World War and resurrected in 1939 by the Ministry of Information. Virtually all artistic propaganda pertinent to the war was filtered through this department. Its leading lights were Sir Kenneth Clark, Director of the National Gallery, who was head of the Committee and his excellent secretary E.M.O’Rourke Dickey, an artist, eminent art historian and an Inspector of art at the Board of Education. Clark was responsible for hundreds of artists whom he deemed qualified to record the war at home and abroad for propaganda and morale purposes.

He successfully brought together, under one large artistic umbrella, many of London’s art schools, professional groups, and societies, as well as the government and the armed forces. This was by no means an easy task, but with 70% of artists losing their jobs, he was eager to try to find some way to help them. Apart from a number of commercial artists who were actually thriving at this time, everything to do with the production of art had virtually come to a standstill. By commissioning as many war artists as possible, full time and short term, he managed to keep them employed. Records show that when the war ended there were approximately 6,000 works of art produced by over 400 artists.

The WAAC initially had a strong interest in printmaking, but this waned when paper of any quality was classed as a luxury item by the government, and the cost of publishing a print was far higher than the price for a large painting. As a lithographer Ethel did have her work cut out. Despite such set backs, the WAAC bought her lithographs right up to the end of the war. In fact they seemed to bend over backwards to help Ethel. Fortunately for her a member of the committee seemed to understand, and took into account that the way she was now working was completely alien to her since she had always left the business and selling side to her good friend and agent, Harold Wright at Colnaghi’s.

Ethel was hopeless at managing her paper work and often arrived at places without a pass or her obligatory sketching permit. When fulfilling a later commission which involved her visiting Hendon she requested flying facilities to be afforded. This sent everybody at the Ministry into a spin because they had no record of having given her a permit to visit Hendon. The RAF were flabbergasted: how on earth were they meant to give this frail lady rumoured to be in very poor health permission to fly, especially when most embarrassingly, she was not even meant to be at Hendon in the first place? The WAAC helped to gloss this over. They also helped to gloss over her petrol coupons and travelling expenses. Ethel did cover vast areas of the British Isles and she had copious exchanges with the WAAC over her travelling expenses. A Mr. Trenaman, who was in charge of finance at this time wanted Ethel to pay for her own travelling expenses, but Eric Craven Gregory, an excellent artist in his own right, came to Ethel’s rescue and wrote the following in a letter to the committee:

I think the case of Mrs Copley is a very special one. We knew she was in bad health, but she was prepared to carry on notwithstanding. I do not think the fees paid to Mrs Copley are very high considering the work she had done. There was a great deal of detail in it and she carried it out most excellently to the complete satisfaction of the Committee. Indeed her pictures are two of the best we have ever had.

I feel strongly that my Committee would approve of her means of transport taking everything into consideration. The pictures are felt to be of great value to the nation as records and she showed great pluck and determination in carrying them out. I hope in these circumstances you will be able to reconsider the question of expenses.

Much to Ethel’s relief, a memo was released on 30th October 1944 stating Gregory had won his case. With her ill health and the way she worked, travelling the length and breadth of the country, it would have been impossible for her to carry on without a car.

Commissions

Children In Wartime

She was delighted to receive a letter on 12th April 1940 from the secretary of the WAAC, E.M.O’Rourke Dickey, asking her to work for them. She willingly agreed and no time was lost; just four days later she received a commission for eight lithographs at 12 guineas each. Four lithographs depicting evacuation subjects and four depicting WVS subjects. The set of four evacuation lithographs was named Children In Wartime. Contrary to her commission she actually produced five Children In Wartime lithographs: The Evacuation of Children from Southend, Sunday 2nd June 1940, A Nursery School: Watling Park, Boys from South-East London Gathering Sticks in Cookham Wood, London Schoolgirls at Finnemore Wood Camp, and Evacuees in a Cottage at Cookham plus three WVSlithographs: Fire Drill, Hospital Supply Depot at Roehampton and ARP Workers in a City Canteen Run By the WVS. All these were reproduced by H.M. Stationery Office, and apparently bore little resemblance to her original commission. This did happen frequently, but the WAAC never quibbled: they knew she was a professional artist, and happily left everything to Ethel’s discretion, but with one proviso, strictly for propaganda purposes — all her lithographs had to fulfil the WAAC’s prerequisite: “that all was well.” Ethel did exactly this with her series of lithographs depicting Children In Wartime. It was vital to show these young children not only coping with mass evacuation but looking happy within their new surroundings.

Ethel was delighted to receive this commission because she loved working with children. Arriving on the station platform at 6.30am she excitedly joined in the hubbub. Afterwards she said, “It was such a moving sight seeing all these young beings quietly embarking the trains. I do hope I have done justice to the scene.”

Here on this platform, and on many others too, thousands of children were being sent off to stay with total strangers not knowing when they would be allowed home again. Fraught parents put on brave faces and family life came to a sickening standstill. This evacuation was the biggest and most concentrated mass movement of people in Britain’s history. In the first four days of September 1939, many thousands of young people were transported from towns and cities to the safety of the countryside.

Some children found the whole thing exciting and were well looked after. “It was like being on holiday” one child said. Unfortunately, some were not so lucky and did have bad experiences which stayed with them for the rest of their lives.

Ethel’s depiction of the evacuation from Southend is full of energy and surreptitious propaganda. Quite deliberately she has featured a young smiling girl in the right hand corner, full of confidence and ready for anything. The children are calm and collected and most importantly, they all display their name tags and gas masks. Nothing has been left to chance: they will all be safe. For propaganda and morale value this lithograph was exhibited in the War Artists Exhibition, National Gallery in late August 1940 with the following text:

The Evacuation of Children from Southend, Sunday June 1940

Southend, as an ‘unhealthy’ coastal area, is just one of the 120 or so evacuation areas – most of the others being densely-crowded industrial cities and towns. The children, after being lined up at the school assembly points, arrive at the entraining stations in the charge of their teachers and voluntary escorts. Each child brings spare clothes, gas mask, identity card, ration book, and food for the day; and wears a label. More than a million school children have travelled like this, and thanks to the staffs of the local authorities, the teachers and the voluntary workers, the moves have gone like clockwork.

Crown copyright.

In Evacuees in a Cottage at Cookham Ethel shows a young group of children sat happily around a dining table. The text beneath this lithograph is as follows:

Mrs Norris, of Cookham, with five of her war family of seven children from London who had by January of 1941 been with her for sixteen months. Mrs Norris is the ideal foster-parent, and there are very many other householders like her. Over a million children have been moved in school parties from the evacuation areas, and with such large numbers, boarding out in billets must always be the principal means of finding homes for them. Given Mrs Norris’ friendliness and care, town children readily adapt themselves to their new surroundings.

Crown copyright.

Air Raids

Ethel did show the total devastation caused by air raids in a number of lithographs and oils, but they were sterilised versions. The press produced a photograph of her working in situ at a recent air raid. The picture on her easel is Raided Area Stepneyand as she sits working at her easel amongst the debris two very tidily dressed young boys watch her paint. This photograph engineers the impression that “all is well,” both artist and boys are unscathed by the latest blitz of bombs. Ethel and many other war artists knew all to well how awkward it could be to turn up to a bombed neighbourhood, especially when the raid had just happened.

My mother was not always welcome on the scene after a bomb raid and sometimes she had to handle the situation with great delicacy. When she was sent to make a record of a big bomb raid in the East End, she stepped out of her car with her drawing book and pencil and the survivors were hostile, they saw her as a curious journalist making pictures of their devastation and wanted rid of her. She had to explain she was not a journalist but a war artist trying to let the public know exactly what was happening and see for themselves just how people were managing to cope in such dire situations.

Under the subject Air Raids Ethel produced: Raided Area Stepney, AFS City Fire Station, The Wool Exchange, Decontamination Unit at Stoke Newington, Bombed Out Bermondsey, Portrait Of A Girl Bus Conductor and AFS Girl During A Raid On The Guildhall.

In September 1941 The Times correspondent wrote -

Artists And The War On Britain: The incidence of the war on Britain is inspiring a great deal of lively and sincere painting and drawing, far more, indeed, than can find a place amongst the official war pictures at the National Gallery, or in such special shows as that of the London firemen. It was therefore an excellent idea of the Artists’ International Association to organize the small exhibition which opened yesterday in the ticket hall at Charing Cross Underground station.

Many of these pictures record, telling and attractively, things which the artists have seen and by which they have been moved. Miss Ethel Gabain’s “Raided Area Stepney,” shows people gathering their belongings from the ruins, holds the eye.

New Theme – The Important roles women played during the Second World War

The second part of Ethel’s 1940 commission, WVS Subjects is extremely pertinent. The Fire Drill, Hospital Supply Depot at Roehampton, and ARP Workers in a City Canteen Run By the WVS were all part of her new theme to show the important roles women were now playing during the Second World War.

Ethel received a new commission for four lithographs based on women doing men’s work. She approached the WAAC to let her produce more than four lithographs, but to no avail. Fortunately, the WAAC had broken with the First World War policy that all works had to be commissioned, and they openly encouraged artists to submit work on specification for possible purchase. Ethel selected a number of her own subjects covering the work women were successfully carrying out at this time. She had them printed and submitted them for purchase.

At the same time she suggested the following subjects for her four commissioned lithographs: lumberjacks, shipyards, industry, either ferry pilots or shipbuilders. The WAAC agreed that lumberjacks, shipyard workers and ferry pilots were appropriate, but the fourth subject should be reserved for ATS girls working AA predictors, providing this was not already being covered by another artist. Ethel produced the following four lithographs under the title: Women’s Work in the War Other Than The Services: Building a Beaufort Fighter, Captain Pauline Gower, Sandbag Workers andSorting and Flinging Logs.

She depicted these women filling sandbags as a lithograph as well as an oil which was purchased for 35 guineas. The oil portrays Mrs Kellam and her daughter, Edith, two Islington women who both worked for Islington Borough Council. Mrs Kellem is dressed in dungarees, clogs and a cap with a wreath of colourful artificial flowers. Ethel became good friends with the women, especially Mrs Kelly who was a mother of thirteen and grandmother of nine.

She knew the WAAC liked what she produced and was determined to get them to take more of her works. “These women are doing really fine work and they are worthy of being recorded” she wrote in one of her many letters. They purchased 10 lithographs — the four originally commissioned plus, Salvage Workers, Work on a Weir Pump and four prints each of Demolition, Brick Sorting and Chipping,Loading a Tractor at Banffshire Lumber Camp, Women at Work on a Tank and Ferry Pilots, at a cost of 2 guineas each amounting to 32 guineas for 16 prints. “I do feel glad that these prints are to be allowed to see the light of day – after all the human contacts which they involved.”

Captain Pauline Gower of the Women’s Air Transport Auxiliary, 1941

The text underneath this lithograph was as follows:

Women made a fine contribution to victory in the last great war, but on the present occasion they have indeed excelled themselves. In no sphere have they shown greater courage and skill than in the air. The women of the Air Transport Auxiliary, of which Pauline Gower is the leader, have the highly responsible task of flying aircraft between the factories and Royal Air Force Stations. Crown Copyright.

The Air Ministry had a rule which prevented women having anything to do with military aircraft and the RAF refused to allow non service women into the Ferry Pools and the central Flying Schools. They did not consider women had the capacity to make use of the training. Luckily Pauline had an ally in Lt.Col. Sir Francis Shelmerdine, the Director General of Civil Aviation, whom she had contacted with a view to forming a Women’s Section of Ferry Pilots with the Air Transport Auxiliary sometime before the Air Ministry and the RAF had voiced their opinions. Shelmerdine had agreed to a Women’s Section and had sent a memo out saying “I have selected Miss Pauline Gower for the post. She is a very experienced pilot holding A & B pilot’s licences, navigator’s licences, etc, and she earned her living for a considerable time in the hard school of joy riding.”

Pauline’s case was also helped by Lady Londonderry, president of the Women’s Legion, Lord Londonderry Chief Commissioner of the Civil Air Guard, and Captain Balfour, who as Parliamentary Under Secretary for Air announced that, in a national emergency, women would certainly be used for ferrying aircraft.

After much negotiation on Pauline’s behalf, on 14th November 1939 she received a letter from the Director General of Civil Aviation directing her to recruit eight women pilots to staff an all-women pool at Hatfield Aerodrome in Hertfordshire. She was elated. The establishment of the women’s pool was the first purely civilian group of ferry pilots.

Pauline was promoted to First Officer Class A, with the designation of officer in charge of women, with a salary of £400 a year, and it was at this point the Women’s Section of the ATA was born. Pauline was the first woman to be allowed into, let alone fly, a Royal Air Force aeroplane, and the Women’s Section of the ATA was the first and only wartime unit in Britain to organise and harness its reserve of female pilots.

Ferrying in wartime Britain was not easy. There were no radios for security reasons which meant there was no communication with headquarters to obtain information about the weather, enemy action or navigational problems. The ferrying changed from local deliveries to supplying the training squadrons in the north of Scotland and throughout the excruciatingly cold and wet winter months of 1940–41 the women ferried the open cockpit, single engine Moth trainers north. The only protection was a small windscreen. “None of us will ever forget the pain of thawing out after such flights.”

Ethel’s lithograph of Captain Pauline Gower shows a close up view of her small windscreen and another lithograph named Ferrying Pilots gives some idea just how open the cockpit was to the elements.

In the first year the section had grown from nine pilots to twenty-seven and when asked about the fine flying record of her pilots, Pauline said “The secret of their high standard of performance is accurate flying and great care. Yet we have never been behind with our deliveries.” By the end of the war the ATA had 166 female pilots.

Lumberjills in Scotland

With a little help from Peter, Ethel decided to make the long journey up to Scotland in 1941 to visit and draw the lumberjills in Pityoulish and Banffshire Lumber Camps, and in so doing she produced two lithographs, [Sorting and Flinging Logs at Pityoulish] and [Loading Logs on a Tractor at a Banffshire Lumber Camp.]

Sorting and Flinging Logs at Pityoulish

The text underneath this lithograph was as follows:

‘Women lumberjacks at Pityoulish lumber camp. They are sorting out timber and flinging each tree-trunk on to the right heap. This is, indeed, heavy work even for men, and it may well be a matter of pride to us all that women have come forward to undertake it as a service to the nation.’ Crown copyright.

At the same time Ethel was producing her war images she was also helping to raise money towards the war effort. In 1942 she exhibited at Hertford House (in normal times the house of the Wallace Collection.) The exhibitors included many of the best-known artists of the day who were giving half the proceeds of sales to Mrs. Churchill’s Red Cross Aid to Russia Fund.

Oil Paintings

Ethel also created many oil paintings for propaganda reasons. A Crèche shows a number of happy babies being well looked after by their nurses whilst their mothers are working hard towards the war effort. This painting took longer than usual as Ethel was very ill and had to have a kidney operation whilst working on it. When it was completed she was advised to convalesce and get her strength back. She did for a short time and then immediately became involved with another commission. This was for an oil depicting a Stannard Pack for burns treatment and although she was only commissioned to do one oil painting she produced two. This commission involved her visiting RAF Hendon in early December. Her reason for producing two paintings was she wanted to illustrate the use of the Stannard medical equipment both on active service airmen and within a hospital ward. Both oils were accepted, one for 25 guineas (the original commission) [A Bunyan-Stannard Irrigation Envelope for the Treatment of Burns being applied by Sister Roberts in Middlesex Hospital,1943–44] and [A Bunyan-Stannard First-Aid Envelope for Protection against Infection in Burns, as issued to the RAF, 1943–44] for 35 guineas.

Sir Alexander Fleming

The same year Ethel suggested to the WAAC that Sir Alexander Fleming and his discovery of penicillin in 1920 would make a good subject for an oil painting. “I feel it should be brought to everyone’s attention how miraculous penicillin is and how it has saved numberless lives during this awful war.” Her intention was to paint Fleming in his lab working on his latest experiment and Ethel received a commission on the 17th May 1944 for the portrait, 50/75 guineas depending on its size.

Ethel painted this picture a year before Fleming shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology of Medicine in 1945. The painting belongs to the IWM but is on loan to the National Portrait Gallery. She spent a considerable time with Fleming painting his portrait, and really enjoyed his company: “he is very intelligent and extremely easy to be with.” While she was walking around a treatment ward with Fleming she had the idea to produce an image showing how penicillin was used. She contacted the WAAC, and suggested she should produce a painting depicting how Fleming actually administered this antibiotic. “I do think the clinical use of penicillin should be shown and he rather feels this too.” Her suggestion came to fruition in A Child Bomb-Victim Receiving Penicillin Treatment, a picture of a young girl, Gillian Samuel, lying in her hospital bed with a drip and her leg raised in a support. Gillian was in fact receiving experimental treatment, and was not a bomb victim. She had been knocked down by a car and was in danger of losing her leg.

Williams & Williams Reliance Works, Chester

Ethel became involved in a number of factory depictions showing men and women working at the Williams & Williams Reliance Works in Chester. She was commissioned to make eight lithographs which were done in 1945. However, Ethel’s ill-health and the cessation of hostilities prevented their publication. These images, Welding a Pontoon Landing Craft, Prefabrication of Lock Class Frigate, Salford Works, Small Pontoon Bridge, Working a Centreless Grinder, Do All Saw, Swinging Sections of a Bailey Bridge, A Tapping Machine Operator and Latheswith their precise details, are some of the finest lithographs Ethel made. She also produced three oils for the chairman, Mr. Ben Williams: Women Welders at Williams & Williams, Machining a Blank for Jerricans and Women Workers in the Canteen at Williams & Williams, (Mr. Ben’s Canteen.) These oils are on display at the Grosvenor Museum, Chester.

Women Welders at Williams & Williams, Chester:

The family firm of W&W was founded at Chester in 1910 and specialised in cast iron window frames. During both World Wars production was switched from frames to other metal products for the war effort. During the Second World War the mostly female workforce made shell cases, shelters, sections of warships, ammunition boxes, Bailey bridges for the D‑Day landings and, most famously, 48 million jerricans. This picture is one of three that Ethel Gabain, an official war artist, painted at W&W’s during the Second World War. The firm later became Heywood Williams Ltd., and the Liverpool Road factory closed in 1995 and was demolished the following year.

Machining a Blank for Jerricans at Williams & Williams, Chester- Charles Robinson, a tool room machinist, operating a Stirk planer.

“Charlie” worked at W&W for twenty-five years. The workers produced around 150,000 ‘Jerry’ cans each week and every millionth can was marked with its number and displayed with great pride in Mr. Ben Williams’ office. President Roosevelt awarded a certificate to the factory, expressing the gratitude of American troops for keeping them supplied with ‘Jerry’ cans. At the outset all the ‘Jerry’ cans were made by Morris Motors in Oxford and sent to Williams’ to weld together with hydrogen gas, but later on the company made the whole thing.

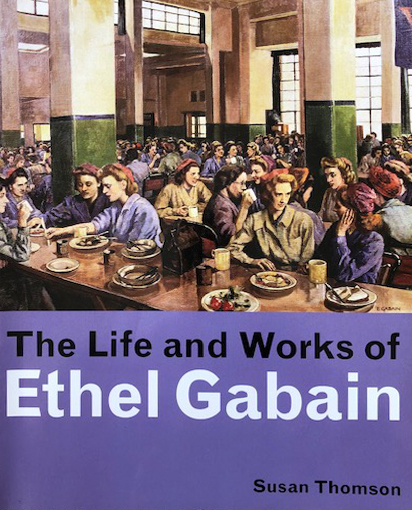

Women Workers in the Canteen at Williams & Williams, Chester.

This large canteen was built specially to accommodate the huge workforce at W&W. It displays a mass of women relaxing in Mr Ben’s new canteen. You can virtually hear their voices and laughter. Many of the girls in this painting are Welsh and Irish. Their fellow male colleagues highly respected the work they produced and openly admitted they could not have carried on without their input.

After the war Ben Williams was knighted in recognition of his factory’s part in the victory.

Ethel refers to the W&W’s commissions in a letter dated the 28th September 1945 to Mr. Gregory (WAAC)

Thank you very much for putting me in the way of this work. Not only was it very welcome but it has been delightful all through, and has led to real friendships both among the Williams and their workers. It has also led to other factory jobs. So thank you once again. She also writes I am going to Manchester on Sunday to do a painting at Ferranti, Hollinwood and shall be away a week or so.

Manchester War Commissions

In 1939, before she became a war artist Ethel had exhibited at the Manchester Academy of Fine Arts and had received the following write up: “The eightieth spring exhibition of the MAFA will open tomorrow at the Manchester Art Gallery, the work of 83 artists will be shown. The exhibits total 343, and the contributors include 37 women. Sisters an Arcadian study by Miss Ethel Gabain, is a beautiful work distinguished by a subjugation in colouring.

Both Ethel and her husband knew the Manchester City Art Gallery’s curator, Lawrence Haward. He was eager to show Manchester’s contribution to the war effort through a number of artists. His main aim was to have records not only of the fighting forces achievements but also of the industrial effort behind the scenes. In an interview with the Manchester Guardian, September 22nd 1945 Haward said:

The upshot of it all was that I resolved to go straight to some of the big industrial firms in the district and ask them to commission certain artists whom I would select for the purpose, to make records of what was considered each firm’s main contribution to the war, which the directors would then present to the Art Gallery. The gallery would have a section of its war records covering the workers on the home front as well as the fighting forces.

The choice of artists was entirely up to me and the choice of medium was only determined when the actual scene to be recorded had been settled. Sixteen prominent and representative Manchester firms commissioned a picture of some aspect or aspects of their work during the war.

Ethel received two commissions from Ferranti Hollinwood, Working on the Cathode Ray Tubes and A Giro Compass, one from Richard Haworth & Co. Limited, Salford, The Weaver, and one from the British Cotton Industry Research Association, The Shirley Institute of Cotton Research. He said the following about Ethel’s patrons.

This was fairly simple when dealing with cotton, where the nature of the work and the method of production were roughly the same in peace-time. The Haworth Mills, for instance, were functioning much as usual, only the cloth coming off the weaving machines was destined for the army. At Ferranti’s three separate productions were recorded all of them connected with different branches of radiolocation. There were four contributions from industrial firms whose productions, though essential to the war, were less in the public eye than those of the firms already mentioned. Amongst these four was the Shirley Institute, Manchester in which one could, as it were, watch industry’s brain at work.

The Ferranti commissions hinged around two women performing vital war work. One worked on the Cathode Ray tubes which played a vital part in radar, and the other worked on a Giro Compass. During WW11 Ferranti’s manufactured marine radar equipment, gyro gun sights for fighters and one of the world’s first IFF (Identification Friend or Foe) radar systems, which vastly reduced the possibility of firing on friendly aircraft or ship. The lithograph depicting workers at the Shirley Institute, Manchester was presented to the Manchester City Art Gallery by the British Cotton Industry Research Association. On the back of her own photograph of The Shirley Institute of Cotton Research Ethel has written: lithograph portraying a number of women measuring the viscosities of starch fractions. It was at this institute they discovered a material resistant both to the malarial mosquito and the Burma climate. A number of her photographs have hand made notes written on the back of them. Sometimes she criticises the way she has depicted something “not enough shading,” “wheel too big,” etc., but more often than not she makes a small note describing the scene and the person depicted within it.

Towards the end of the war in 1945 Ethel approached the WAAC suggesting Caroline Haslett the Director of the Women’s Electrical Association and Freya Stark a British travel writer and expert on the Middle East were “worthy of record.” The Committee accepted Caroline Haslett, but for once did not agree with Ethel’s second choice: they suggested Barbara Ward the Assistant Editor of The Economist instead of Freya Stark.

These portraits are quite different, but their content is similar — both Ethel’s sitters are very successful women, determined to make their own mark on the events of WW1l. Ethel has captured them off-duty. Both wear wide lapels and Barbara’s jacket has an “up market” air about it. Her pose is slightly awkward with her clasped hands held high, but her face is relaxed. Caroline’s appearance is far more sober with her single string of pearls. Everything about Caroline is immaculate. Ethel’s cross hatching and gorgeous thick pencil strokes enhance both the pictures.

Barbara Ward

Influenced by her mother, Barbara became a devout catholic and eventually she became President of the Catholic Women’s league. After witnessing anti-Semitism in Austria and Nazi Germany she began to help Jewish refugees and set in motion Catholic support for any forthcoming UK war effort. She and the historian, Christopher Dawson established the Sword of the Spirit organisation. Using this organisation, backed by an encouraging broadcast by Cardinal Hinsley Archbishop of Westminster, they tried to bring together Catholics and Anglicans opposing Nazism. Through lack of support the scheme failed and the organisation became a wholly Catholic one.

An economist and writer, Barbara became Foreign Editor for The Economist. She also became well known for her books about the problems of economic development in developing nations. She argued for a more even distribution of the world’s economic resources between the industrial and the developing countries.

During the war she travelled widely on behalf of the Ministry of Information spending a lot of time in the USA. Her commitment to upholding Christian values in the war led to The Defence of the West, a series of five broadcasts first published in The Listener. After the war she was a great supporter of the Marshall plan for the reconstruction of Europe.

In 1946 she became a governor of the BBC and of the Old Vic theatre. Four years later she became Barbara Mary Baroness Jackson of Lodsworth after marrying Commander Robert G.A. Jackson but always used her maiden name. In 1973 she and her husband formally separated but never divorced.

Ward’s frequent visits to North America brought her into contact with the political establishment in the United States and she regularly visited the White House during the administration of Lyndon Johnson, although she was totally against the war in Vietnam. She also served as an adviser to Robert McNamara when he became president of the World Bank.

During the 1960’s she tried to persuade the Roman Catholic bishops, all gathered for the Second Vatican Council, to put development issues on her church’s agenda, and she was also part of the group which helped to create the pontifical commission for justice and peace. In 1971 she became the first woman to address a synod of Roman Catholic bishops.

Caroline Haslett – 1895–1957

After taking a commercial course in London Caroline started work early in 1914 at the London office of the Cochran Boiler Company — after four years she was managing it. She left Cochran’s to become the first secretary of the Women’s Engineering Society which in turn led to her involvement in the formation and early years of development of the Electrical Association for Women.

When the EAW turned its attention to domestic electrical equipment Caroline was delighted: she could now fulfil a life long ambition — to emancipate women from domestic drudgery. Ironically during the war and for some time after, in her advisory role for the EAW and the British Electricity Authority, Caroline spent a good deal of her time persuading housewives to save their electricity by not using too many gadgets.

In 1932 the British Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs was formed and Caroline was elected chairman. Three years later it was decided to drop the word Clubs from the title and it became known as The British Federation of Business and Professional Women with a committee that was able to speak collectively and authoritatively on all matters affecting professional and business women. Caroline was its first chairman and she made sure everybody knew her feelings when she stood in front of a packed hall and made the following statement “The barrier between professional women and women in industry is completely artificial.”

When the war finally broke out she became an advisor on how to help and train women for all kinds of war work. Before the war, in 1938, she had been asked to visit the AA batteries at practice and advise the commanding officer, General Frederick Pile, if any of these jobs could be held by women. Except for the heavy work of loading ammunition, she reported that women could man search lights and fire control instruments.

During the war there was a vast increase in the number of women in industry and the Women’s Services. The W.R.N.S, the A.T.S. and the W.A.A.F. all consulted Caroline on the welfare of their girls. As Chairman of the War Workers’ Clubs Committee she helped set up social amenities for young women away from home. With Ruth Tomlinson she formed the International Women’s Service Groups to foster a spirit of goodwill among women of different nations. Culture centres were set up where refugee women from all counties could freely meet. A register showed 546 women representing 26 countries were found some kind of employment by Caroline as adviser to the Ministry of Labour. She also made sure these women were prepared for their return to their countries. Courses in hygiene, sanitation, child welfare, nursing, were provided. Many British women volunteered to go into Europe immediately it was liberated and help with reconstruction work.

Always an engineer at heart Caroline loved ships, and in 1949 the BEA decided to name their first collier after her: The m.v. Dame Caroline Haslett, built at the Hall Russell Aberdeen Shipyard. In 1953 Caroline was elected Chairman of the British Electrical Development Association.