My parents died 35 years ago, when I had the following images of them: my father as a semi-invalid, semi-recluse, of great charm, culture and gentleness, an artist whose genius was inadequately appreciated; my mother as beautiful, French, ebullient, crazy, a petite figure who organised our lives, cooked marvellously, cared for my sick father and who painted flowers and portraits because they were easiest to sell, thus leaving my father free to create master-works which didn’t have to sell because hers, though no master-works, did.

Much of this crudity I now realise was the truth as I wanted to see it – my father a noble god, my mother a lovely handmaiden – rather than as it was. In fact, my father’s lithographs sold just as well as my mother’s and later she made flower paintings not just for money but also because she enjoyed painting them. Again, in the last 12 years of her life my mother was increasingly ill and though she continued to work with humour and tenacity it was my father who physically cared for her in her periods of incapacity: he grew stronger by necessity and became a healthy old man.

Indeed when they were both fairly old and I was in my supposedly vigorous thirties I marvelled at the guts and energy of both of them. My mother would set off to a committee meeting or art gallery liable at any moment to pass out from the temporary failure of her one remaining kidney or just to seize up from arthritis. My father started to go out into the world, to enjoy dinners and wine and brandy. In the late 1940’s when he was President of the Royal Society of British Artists he knocked on Vivien Leigh’s theatre dressing room door, asked her to open the Society’s annual exhibition, and of the resulting crowd at the Private View I doubt if more than half ever got inside the gallery and the press, of course, had a field-day.

My mother, part French part Scots, brought up in Le Havre was sent at 14 to an English boarding school for girls. She never quite reconciled her ebullient, reckless self which took her often in her youth to work in various Paris studios, with her respectable self which told her to be a nice English, middle-class person. Thus, though she and my father were firmly agnostic, her Scots blood produced waves of Protestant conscience whereupon my brother and I would suddenly be dressed up and taken to Sunday service; but the impulse and hence the church-going never survived long. We were sent to a public school at much financial sacrifice: my mother, like all parents in turn, was invited to lunch with the Headmaster, where, perhaps after a sherry too many, she mistook a conversation about Homer’s Odyssey to be about James Joyce’s Ulysses which, unlike the Odyssey, she had just read, and she launched into a daring eulogy of Irish social liberation: no one was amused. She longed for my brother and I to go to Oxford or (indeed, if physically possible, and) Cambridge; but when I left school early to become an actor she switched at once and, seeking to advance my career, cultivated famous theatrical figures, invited them to dinner, painted their portraits – that of Lilian Baylis now in the bar at Sadlers Wells is by her. Though she could be embarassingly interfering and she and I had many rows about this, yet in the end her warmth and fun were irresistable. I think of her as like Ellen Terry, impatient of stupidity but with a deep, warm femininity. I have a memory of the day of George VI’s coronation in 1937: she told me she had had a lovely, peaceful morning painting Carmen (who was her favourite model) while they both listened contentedly to the wireless commentary. She had impulsive loyalties: after hearing the final speeches broadcast on the eve of the 1931 general election she said, “We must all vote for Ramsay Macdonald, he’s nice and Scots and sounds so tired, poor man.”

In the mid-thirties when finances were low my mother had the idea to tour girls’ schools giving lectures on the art history of whichever country was the subject of the current RA winter exhibition. She knew no history so my father, who did, wrote the lectures and she learnt them by heart, and armed with a lot of slides then delivered them with theatrical panache. Questions were a bother because she knew no more than had been set down for her, but she never faltered, became very popular and after a couple of years couldn’t cope with all the bookings. Her one rule was to go only to those places from which she could get a train home the same evening to be back with my father.

In the 1939–45 war my mother was an official war artist recording women’s work. She was often sent to factories, farms and camps in remote areas and the physical effort as her health declined was considerable; my father if possible would go to look after her. When with age and illness she grew very thin she worried about her appearance and turned to eccentric hats, blue rinses, some sinister black stuff which she brushed on her hair with a tooth brush, white face powder and dark red lipstick. Then she set out to wherever she had to go.

My father remains more elusive, as though protected by his invalidism and the veneration which as a boy I felt for him. A sort of calm surrounded him: whether he was himself alwavs calm I don’t know. His activity was gentle and free: he would kiss my mother tenderly and unselfconsciously with me or my brother in the room. I don’t ever remember him angry. Once, years later, he phoned me to express keen disappointment that I had forgotten my mother’s birthday – this when she was old and ill: I was shocked equally by my own forgetfulness and the strength of his feeling. Each subsequent year until her death he rang a week in advance gently to remind me.

My contact with him was in conversation: even as a small boy I knew I could ask any question, however silly, and he would discuss the subject seriously with me as an equal. When I began acting he would draw analogies between acting and drawing, analogies which seem simple and obvious now but impressed and helped me as a student beginner. For example, an artist can suggest colour even when drawing in black and white; similarly words which are neutral until used may literally be given colour by a speaker. He would show me the sketch for a print, next the finished print, next the subsequent states and would then talk about the initial idea for a picture, it’s first bare statement on paper, it’s development and elaboration, and finally the wonderful experience of elimination and simplification; the process of studying and rehearsing a part is of course analogous.

My housemaster at Westminster, D J Knight, formerly a Surrey cricketer had written a book on batting illustrated with photos of himself demonstrating strokes. This fascinated my father who pointed out that when a skilled man executes a movement perfectly adapted to its purpose, the vision is arresting: the problem is how to recapture it on paper or on the stage. My father’s observation was acute: he and I went together once only to watch polo at Hurlingham in 1938 (one of the players was Lord Louis Mountbatten). That evening he made a few pencil notes and over the next few years produced paintings and many etchings, all of polo players in action and all from that single afternoon.

My father printed all his own and my mother’s lithographs until even with her assistance he could no longer manage the heavy press, when he turned to etching and painting. As children we were involved as helpers and I remember the mysterious chemical process by which the picture disappeared from the stone: then the roller was inked and my father would thump it down on the corner of the stone and then roll over the stone with firm, slow pressure, repeating the thump and roll in every direction in turn: the picture had by then re-appeared. After my brother and I had helped turn the big, spoked wheel which took the stone through the actual press and back again, we would watch the weights and blankets being removed and finally there was the magical moment when my father slowly peeled the paper from the stone, looked at it circumspectly and then – less exciting for us – discussed the resulting print with my mother. Later the grainer would come to the house, lay a wooden board over the bath, place on it the old stones and with a kind of phallic pestle and fine sand begin to erase the used drawing and prepare the surface for further use.

In 1925 when my brother was 7 and I 10 the family left England. Doctors said my father, who was then really ill with a heart condition, would be better in a warm climate. So my mother organised the business of moving us all for an indefinite period to Italy where the pound then bought a great many lire. We went by ship because again it was said my father would benefit from sea air. My mother was exhausted by the time we set sail and looked forward to a rest on board, but within 24 hours we hit a storm in the Bay of Biscay and she, my brother and I lay seasick and groaning in our cabin. Enter my father, upright and radiant: “Oh, you should be on deck, the waves are magnificent.” (Pause, then to my mother quite gently) “Carina mia, I’m ashamed of you just lying there.” I think she would have struck him had she had the strength.

Alassio, then a friendly little Ligurian town, had been decided on as our destination. We arrived, booked into a hotel and my mother went out to find us a home. Within 6 days she had us installed in a small rented villa on the hillside overlooking the Mediterranean. I can understand how dialects become transmuted: my mother, fluent in French but with no Italian, evolved her own sounds of communication full of invented Franco-Italian words which she used with such conviction that even Italians sometimes adopted them, if only out of courtesy. My father spent his time in the garden of the villa, reading and working: no heavy stones, only lithographic paper which I remember thinking must be a very poor substitute. He wore a curious pair of loose silk pyjamas and his naturally olive face burned black in the sun. The small English community, who all without exception took drawing lessons from my mother, would whisper, “Did you know that our nice Mrs Copley is married to a MOOR?”

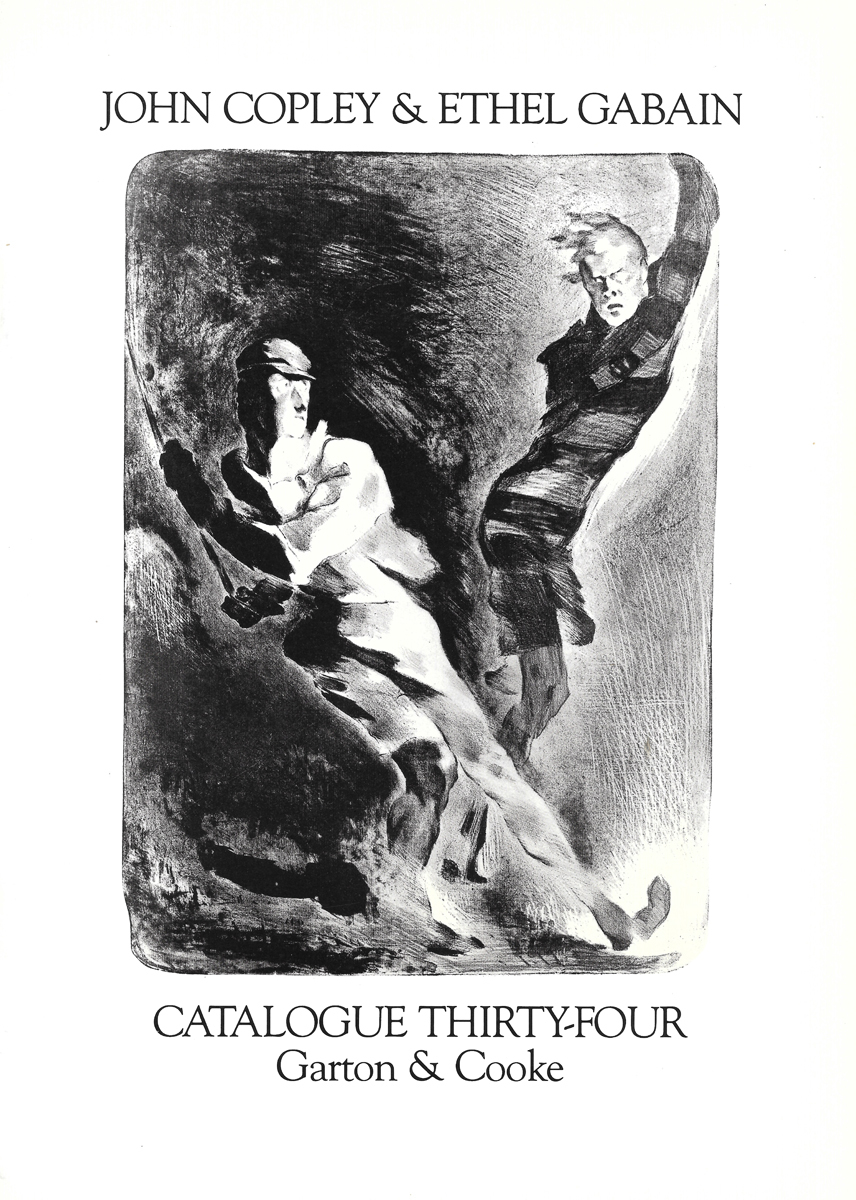

I said earlier that my childhood image of my parents was twisted: it was. In particular the artistic image of my father as a protected, patriarchal genius, of my mother as a charming lightweight, making whatever was commercially convenient. This is absurd: both were superb printmakers, master lithographers, worthy members of the Senefelder Club which my father had helped Joseph Pennell to found. Their characters were quite dissimilar, but they complemented each other in every sense. They enjoyed discussing each other’s work and helped one another, but though they worked in the same medium, in the same studio, their styles remained distinct and entirely individual.