In art, the conventional signals are usually pretty reliable. A glance at the reference books will establish an artist’s nationality, his dates, where he studied, and what media he worked in. From that one can make an educated, and as a rule quite accurate, guess at the sort of artist he will be: the pigeonhole is ready and waiting. But every now and then along comes an artist like John Copley, designed by fate to upset all these confident calculations. What would the reference books tell us about Copley? That he was English, born in 1875, died in 1950, that he studied at Manchester School of Art and the Royal Academy Schools, and that he was primarily a printmaker, of lithographs and etchings. They might also confide that he was a founder of the Senefelder Club, vowed to the encouragement of the artist’s lithograph in Britain, and that towards the end of his life he was President of the Royal Society of British Artists, a body of impeccable conservatism.

So, surely, we have him taped. We would not, admittedly, know how well he did what he did, but the signs all seem to indicate something rather cosy, comfortable and parochial: the sort of pleasant minor artist that makes aficionados of the currently fashionable Modern British dissolve in a rosy, nostalgic glow. From this sort of reassuring received notion it is deeply alarming to come to the work itself. The image we would probably have of an English print-maker active from 1906 on would be an amalgam of “the Stamp of Whistler” and the pernickety, mysticised historicism of F. L. Griggs. Something, anyway, very local: the kind of art that notoriously does not travel well. It might come as a surprise that in this, the heyday of British etching, Copley was practising almost exclusively as a lithographer (the etchings came much later), but even that, in and around the Whistler circle, would not be entirely unprecedented.

What we actually encounter in Copley is an unmistakably cosmopolitan figure, who has little or nothing to do with the traditional print-making of his own day in Britain. About the nearest one can come is to the shrewd, unglamorous observation of Sickert’s etchings, but the neat, tight pictorial language of Sickert is very different from the largely emotional checks and balances of Copley. And indeed, in general there is little or nothing which would identify Copley’s work as being necessarily British. His artist wife, Ethel Gabain, was half-French, and for reasons of his health they lived some years in Italy, where Copley had studied earlier and for which he had overwhelming admiration and respect. So, one might perhaps look for French or Italian affinities in his work. But here too one would be disappointed, apart from the almost obligatory nod of the lithographer towards Lautrec. The closest connection, indeed, especially with the later work, seems to be with Germany, especially the Germany of the Neue Sachlichkeit. But here also, for whatever reasons the comparison springs to mind, it is clearly not quite right. With no clues to the origin of the prints other than internal evidence, one might hazard that they came from somewhere within Germany’s sphere of artistic influence – Czechoslovakia, say, or Hungary – and leave it dubiously at that.

Which is really only to say that Copley is an unclassifiable original. Given that, the next question likely to come up is of whether he can be regarded as an important artist or not. Here, a certain amount of snobbery relating to medium has to be dealt with. Though Copley was trained as a painter, and did paint rather well from time to time, there is no doubt that his heart and the best part of his creative work went into his prints. It is sometimes felt that this in itself imposes a limitation. It is really only another version of the argument over whether Chopin can be a great and important composer if he “only” wrote for the piano, or whether the greatest sonneteer in the world does not somehow fall short of even a rather unsuccessful epic poet.

Confronted with a representative selection of Copley’s prints, however, all this seems completely irrelevant. It is, after all, not the size of the work which determines one’s view of its value, but the richness and individuality of the vision. And here there is no doubt that Copley has very strong claims to our attention. If he has been somewhat over-looked since his death, mainly on account of his central devotion to printmaking rather than painting, there is no reason whatever that the neglect should continue, in an age where, for example, the linocuts of Claude Flight and the “Grosvenor School” of his followers, long regarded as an eccentric by-product of crafts-for-schools, have been restored to their rightful place as a central expression of the modernist spirit in Britain between the wars.

The first thing to strike one about Copley’s early lithographs is the extraordinary originality of their imagery. If we take something like A Lavatory of 1906 we immediately find ourselves in the presence of someone with, to say the least, a very idiosyncratic vision of life. These men washing and arranging and preening themselves behind the scenes, away from the womenfolk to whom the height of masculine elegance and style is always meant to seem casual and accidental, could well be the subject of a cartoon by Phil May or George Belcher. The surprise is to see such a theme handled in “fine art” style, an intricate and ingenious composition which throws just enough but not too much emphasis on the impassive figure of the attendant at the rear, and enables the artist to stick at amused observation without going over into social satire. As often in Copley’s work, there is an element of slightly sardonic humour about his approach, but making general socio-political points hardly ever seems to be his aim. Rather, he is fascinated by his subject, as a dispassionate observer, and then, more importantly, he becomes absorbed in the pattern he can make out of it, the sometimes bizarre shapes he can find in it.

These shapes, though, are rarely exploited for their own sake. We may sometimes remember that Copley was only three years younger than Beardsley, and underwent many of the same ninetyish influences, but his use of the extraordinary and perverse silhouette, the strangely intense and ungainly couplings of figure with figure, will remind us, if of anyone, more of Egon Schiele. Particularly is this true of his work during the First World War – indeed, right through from Athletes Dressing of 1912 to Tennis Players of 1918. Though he shared with Sickert a fascination for the music-hall and the theatre in general, the artistic results of the interest were very different. For one thing, Sickert is much more interested in the audience than Copley, who is absorbed in the magic of theatre and the making of that magic, even to the extent of deliberately demythologising it in compositions like Footlights (1911), which cheerfully, unflatteringly, shows how it is all done, or A Dancer Panting (also 1911), in which the anti-romantic title is backed up by the sympathetic but unsentimental image of the slightly overweight, slightly over-age dancer not taking the interval quite so easily as her fellows.

If the phantom of Schiele is sometimes in evidence (only in our eyes, presumably, since it seems unlikely Copley was familiar with his work), elsewhere other Germanic ghosts occur: Kollwitz, perhaps, in Raising Hammers (1914) or Recruits (1915); Willy Jaeckel in the more overtly symbolist Bearers and A Man (1917). But the attitudes of Copley towards his subjects are quite as complex as the unlikely Schiele/Kollwitz/Jaeckel comparisons would suggest especially as they also have to include, as the Twenties progress, a touch of Grosz and/or Dix. It may be said at once that Copley is not noticeably warm and compassionate

towards the human predicament. His characters sometimes seem faintly marionette-like: we may remember also that he was only three years younger than Edward Gordon Craig, and wonder whether he was not occasionally, in his management of the human drama which passed before his observing eye, a sort of theatrical ringmaster making his Ubermarionettes jump through hoops of his own curious devising.

And yet he is not unsympathetic. He is rarelv if ever a satirist. Whatever we might make of a subject such as Lacrosse (1910), for instance, it is not simply a joke at the expense of the players, nor, it seems, a criticism of them for doing what they do. No doubt there is an awareness of the ridiculous side of this, as of all sporting activity, but the image also has unexpectedly sinister, demonic overtones; and, looked at in another way, it is surely more about the amazingly dynamic shape that the two players make, moving in opposite directions towards the same general end, than it is about the lesser, human aspects. And ultimately, of course, it is about both: it can be read, with splendidly controlled ambiguity, on several different levels.

Another area of mastery in Copley’s work is that of scale. If one takes The Ambulance (1918), it can be seen immediately as a frieze-like composition of remarkable force and sparse grandeur: it is large (44 x 55 cm) and occupies an extensive mental space. He can with equal skill move into a tellingly selective medium shot, as in Spectators at a Tragic Play (1920), where the expressions of the four visible members of the audience are not only vividly caught, but admirably made part of a composition powerful in itself as well as for what human information it conveys. And with A Drink of Beer (1920), we come to something altogether more tightly packed, using again almost cinematic means to isolate and concentrate: in this case on the expression in the eyes of the girl drinking the beer. This print in particular makes us aware of something we are only faintly conscious of in the other works cited: the interior dynamic of the image which resides in its having captured and isolated a moment plucked from time. Even with something as formal-seeming as The Ambulance, what we are actually seeing is an instant of arrested action such as the camera might record. Other factors in the type and degree of stylisation affected by Copley militate against our ever being tempted to describe his work as photographic, but nevertheless it often has the photograph’s ability to freeze an action and hold it in perpetual potentiality.

This feeling that much of Copley’s work creates brings us back to the theatrical metaphor: it is as though he is staging scenes to express his own vision of the world, and so confiding to us pages from an unwritten drama. This is perhaps especially true of the lithographs: there seems to be an observable shift of emphasis once, in the early Thirties, he has moved over largely, then exclusively, from lithography to etching. Certainly the new medium brings out new aspects of his talent. The underlying view of the world remains much the same, and equally difficult to pin down. The unease one senses in many of his early lithographs has sometimes been attributed, as in the case of Books (1915) and Tennis Players (1917), to some kind of latent social message (that the pursuits of the young men in them are irrelevant and irresponsible in time of war, for instance), but despite his later appearance in such contexts as the 1935 Exhibition against War and Fascism, it is difficult to attribute it to any structured set of social or political or even religious, attitudes. Rather it seems – and the etchings bear this out – to be a more existential kind of unease, a suspicion that things are never quite what they seem, motives are never clear-cut, and value judgements shifting and unreliable at best.

In all of this Copley seems like a very European figure, dissociated from both the smugness one often senses in the socially committed artists of interwar Britain or the frank escapism of the rest. His is an art vitally and (some landscapes apart) almost invariably connected with human beings and with social life. But he sees nothing as straightforward and unequivocal. He delights in his etchings to dismember his subjects, cropping their bodies in strange places. An extreme case is Figures in the Wind (1940), where the two figures are thrust unceremoniously into the frame, spilling over at top and bottom and on either side. Socially oriented critics might see the year in which this print was made as significant. Whether it is some sort of oblique comment on the Second World War or not, it is uniquely unsettling.

It is also symptomatic of a widespread tendency in his etchings to be looser, more obscure and generally more difficult of approach than his lithographs. Of course, the external circumstances of his professional life may well have also had something to do with this. His lithographs were widely shown and were for him an important means of making a living. The etchings, on the other hand, were little shown or known during his lifetime, were seldom formally editioned, and seem to have been made primarily to satisfy himself. His son Peter Copley recalls in his childhood and youth somehow automatically regarding his father as the protected one in his parents’ marriage, while his mother “painted flowers and portraits because they were easiest to sell, thus leaving my father free to create master-works which didn’t have to sell because hers, though no master-works, did.” He admits, however, that this was perhaps the truth as he wanted to see it rather than as it was: John Copley’s lithographs certainly sold as well as Ethel Gabain’s, and if her subject matter was more obviously “popular” than his, that was primarily because that was what came naturally to her.

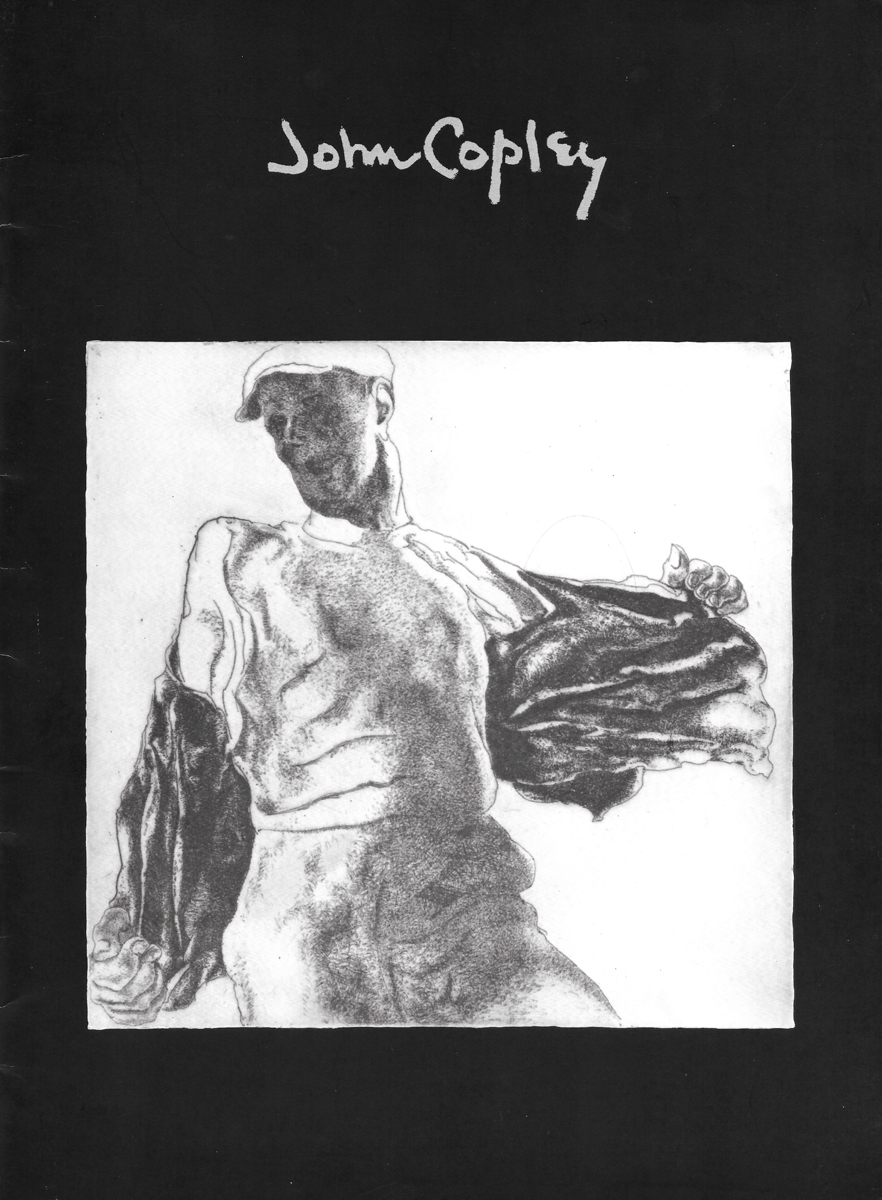

All the same, it is clear that in the latter years of his life Copley did tend to retreat and become more introspective, in his work and his life. It is this that gives the etchings their compelling weirdness. Even when Copley is observing something everyday, as in In the Tube (1948), it is something strange and unaccountable about the situation – the two women sitting side by side but completely, almost wilfully, discrete from each other – which catches his and our imagination. Another rendering of the buffeting of wind on people, this time called simply Wind (1947), has the new fluidity and irreducible strangeness, while A Man Pulling Off His Coat (1948) takes on a quality at once monumental and obscurely ritual which cannot be fully accounted for in the gesture captured, which is in principle simple enough. Sometimes the subject is accountable, and all that remains mysterious is the artist’s attitude towards it: in London Snow (1940), for instance, where the woman in the foreground seems to have sat down rather too suddenly and the two men behind look with alarm (surprise? amusement? concern?), or French Songs (1946), in which the singer standing back to the piano looks tense and rather ghostly, while the accompanist and his page-turner are presented in a deadpan fashion which does not preclude our finding the whole scene funny but does not either imperatively require us to do so.

Blackish humour and existential unease: these have been in various combinations a staple of British art in recent years, but, except for occasional moments in the work of the British Surrealists (with whom Copley otherwise has virtually nothing in common) it was not a combination much favoured, or even much recognised, in the heyday of Copley’s etching-say, from 1932 to 1949. In any case, it was a curious time to be shifting one’s interest towards etching, at the very moment when the majority of graphic artists were moving confidently in the opposite direction. One suspects some built-in contrariness beyond the consideration of health and the physical strength required by a lithographer. Also, probably, a conscious desire to shift from a “painterly” medium like lithography to something more energetically linear.

In any case, by taking up the medium at a low ebb in its fortunes, Copley did give himself a remarkably free hand. Since so few were working principally on etchings at the period, there were few conventions to be flouted and fewer expectations by the public to fly in the face of. If Copley had sought a medium in which he could happily commune with himself and never think about sales or communication in a broader sense, he could hardly have chosen better. The lack of constraint and freedom of utterance which result are tonic. Copley, after all, as we can tell immediately from the lithographs, was a man with a natural oddity of vision, as well as a passionate interest in artistic technique. When these come together in the etchings, we get print after print of startling individuality. With this goes great stylistic confidence.

Too many British artists of Copley’s generation are worthily, modestly busy cultivating their own garden, observing the proprieties, watching to see that they remain consistent. Copley, for better or worse, is not like that. Though he could hardly be more different from Picasso in the scale of his operation or in temperament, he does have one thing in common with the Catalan master: he sees what he sees, picks on whatever style takes his fancy to express it in, and grandly takes it on trust that the result will be recognisable as his work because he, after all, is the creator. And in this he was entirely correct. Sometimes his paintings may seem to speak the language of the tribe, though even here there are touches of ingrained singularity which make one stop and consider. But once one is alerted to Copley and his work, there is little danger that his prints will be confused with anyone else’s. All possible snobbery about media, major or minor, instantly evaporates: unmistakably, Copley is the real, right thing.