From 1906 until his death fifty years ago in 1950, John Copley dedicated himself to making prints. This exhibition is devoted to his lithographs and follows that of his work as an etcher held at The Fine Art Society in 1998.

Like Whistler, John Copley completed a significant body of work both in etching and lithography. Their careers differed in that Whistler was an etcher who took up lithography, while for Copley lithography came first. Like Sickert, Copley was fascinated by the theatre. Also like Sickert, he was prolific and technically adventurous. It is equally difficult to place him in his time: he was neither really a traditional artist, nor part of the avant-garde. John Copley also shares with Whistler and Sickert the distinction of originality.

John Copley made over 400 prints, 253 lithographs and 155 etchings. It was in lithography that he made his first statements as a professional printmaker, 31 works published in 1909. The medium allowed him both to work on a large scale and to use colours. He was then 34 years old. He had studied at the Royal Academy Schools from 1892 to 1897, but a chronic heart condition had repeatedly interrupted his attempts to start a career as an artist. Nevertheless, he was one of the most prolific printmakers of his time. He printed the editions of all his own works, as well as those of his wife Ethel Gabain, who made over 300 prints herself. When the heavy lithographic press became too much for him, he turned to etching and found the process less taxing.

No other artist then working in lithography, with the exception of Nevinson, shared Copley’s ambition

Gordon Cooke

John Copley was born Herbert Crawford Williamson in 1875, the only child of William Williamson, Professor of Botany at Manchester University and his second wife Annie Copley Heaton. Copley was always his working name, but this was not formalised by Deed Poll until 1927. He met Ethel Gabain at the Senefelder Club and they married in 1913. The club, named after the inventor of lithography, was founded in 1908 to revive interest among artists in the medium. John Copley was its first secretary, but resigned from the club in 1917 following a disagreement over whether it should adopt a more commercial approach.

His lithographs were shown at the first Senefelder Club exhibition held at the Goupil Gallery in 1910. In 1914 the Goupil Gallery mounted a joint exhibition of lithographs by John Copley and Ethel Gabain. The following year Harold Wright, who ran the print department at Colnaghi’s, approached Ethel Gabain, suggesting that her work might be better represented by his firm, and in due course Colnaghi’s also took on John Copley. The association lasted over thirty years, and Harold Wright became the authority on both artists’ work. He compiled the first catalogue of Copley’s lithographs, covering the period up to 1923, which was published in the catalogue The Lithographs of John Copley and Ethel Gabain, Albert Roullier Art Galleries, Chicago 1924. He maintained a manuscript list in continuation of this, and the full catalogue is published here for the first time.

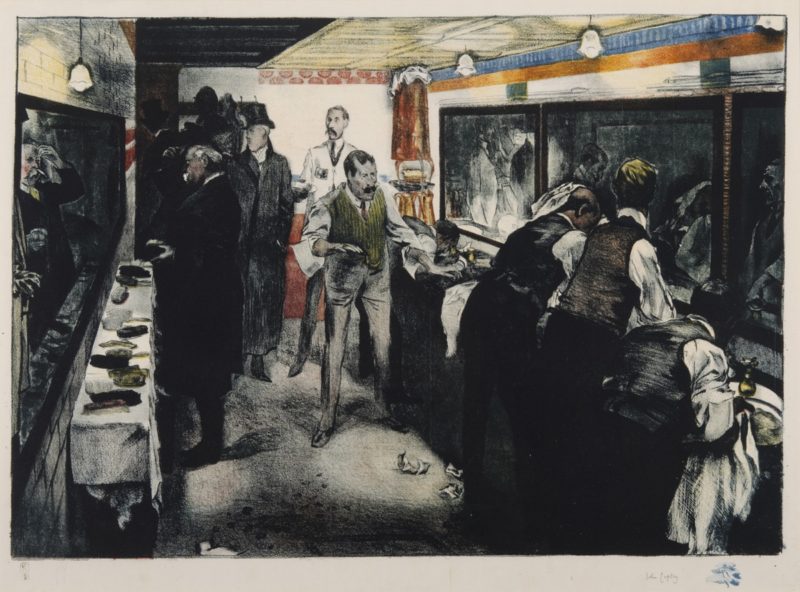

The Lavatory 1909 [2] was shown at the first Senefelder Club exhibition, and an impression was bought for the Victoria & Albert Museum. It was John Copley’s first colour work and one of the most complex. Printed in seven colours, it shows a scene in the lavatory beneath the Empire Leicester Square, London. A number of men prepare themselves for the evening under the detached gaze of the attendant. Two further colour prints followed, A Tea Shop [3] and A Daylight Lamp [4], but the response from the public must have been disappointing, and Copley reverted largely to black and white. In 1910 he produced perhaps the first truly modern print in Britain, the monumental Lacrosse [10], a work inspired by a match played by two visiting teams from Canada. The Surgeon 1911 [15] is printed in four colours and shows the operating theatre at the Military Hospital, Millbank, London. Athletes Dressing 1912 [16] is the most elaborate of all the colour prints, a painterly image which dispenses with black entirely and uses thirteen colours.

In 1914 Copley made a series of ‘Studies’ of his wife at home [18–20] and then his final colour prints, inspired by a day at Epsom Races, In the Paddock and After the Finish [21 and 22]. Such domestic and carefree subjects were left behind as the First World War altered the world he observed. Copley’s first response was Recruits 1915 [23], a study of a squad of men marching, still in civilian dress. The men, some old and others little more than boys, are each closely observed and their faces fully realised. The artist himself, who was thirty-nine when war broke out, volunteered for active service but was turned down on medical grounds.

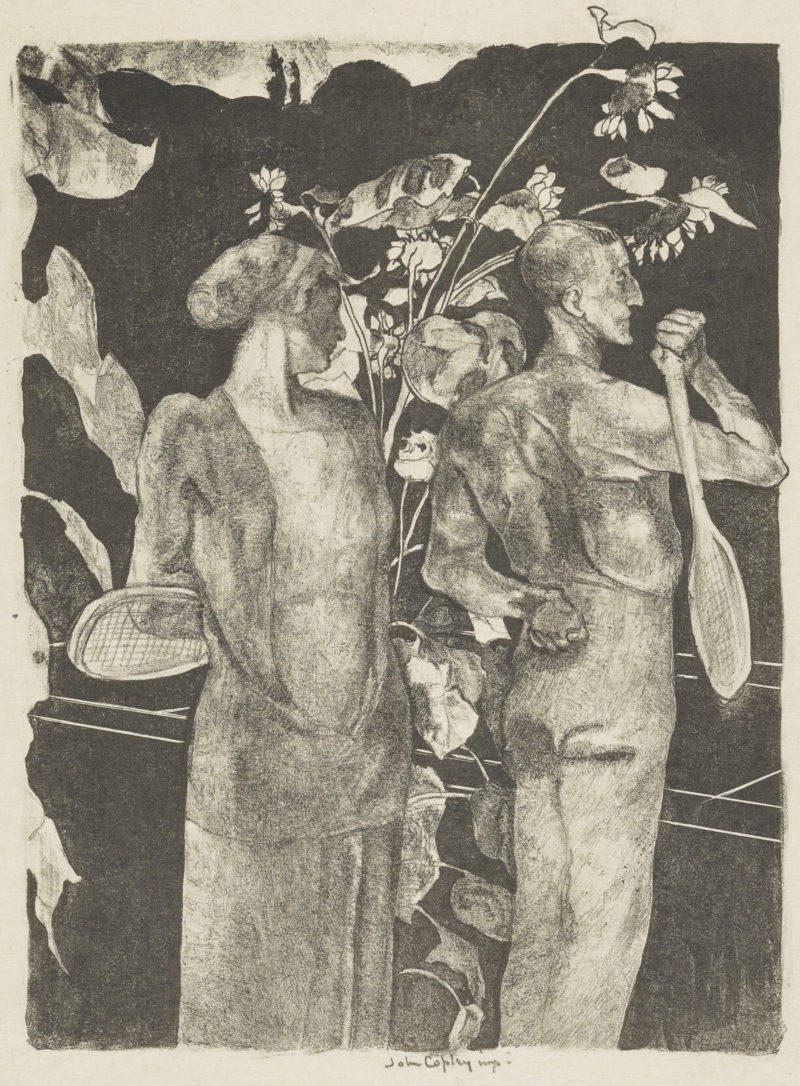

Although the subjects he chose between 1914 and 1918 did not all reflect the war, in contrast to the pre-war works, many of them convey a sense of unease, such as Books 1915 [24], Tennis Players 1918 [31] and Five Girls 1918 [32]. In each of these designs the postures and gestures of the figures create an atmosphere which is highly charged. The Ambulance 1918 [33] is one of the largest lithographs. It shows a wounded German prisoner being lifted on a stretcher by four uniformed orderlies from a Red Cross ambulance, the scene frozen as a camera might record, but stylized in a manner which is far from photographic.

In 1919 and 1920 John Copley suffered a recurrence of his heart trouble, was confined to his home and forbidden from even drawing for more than an hour a day. He made smaller works during this period including a series of Madonna subjects suggested by his reading of Dante’s ‘Vita Nuova’ [34 and 35]. A Drink of Beer 1920 [36], like The Ambulance, has the immediacy of a photograph but the relationship between the figures is curious; those in the foreground and distance are present but detached. The man seems animated by his story while the girl drinking beer looks away.

The heart condition continued to affect his ability to work and between 1925 and 1927 John Copley spent two years living with his family at Alassio in Italy to try to restore his health. Alassio: Starry Night 1928 [40] returns to the scale of earlier works and the monumental quality which he often sought. The head in the foreground is Battestina, an Italian model also used for some etchings of this period.

Increasingly etching took the place of lithography as Copley’s principal medium, partly because the press required less of his strength. Nevertheless he made nearly forty lithographs between 1928 and 1938. With glimpses of street, café and theatre life, he returned to the vocabulary of his pre-War work and in 1933 he made his first two self portraits, one full face, the other Seen in a Mirror [49 and 50].

In 1935 Copley produced one of his finest works The Foyer [51] in which four women wait outside an auditorium, standing on a strangely tilted floor. About this time he resumed painting after nearly thirty years. Ethel Gabain had already taken to painting and engaged a young model, Carmen Hyde, who sat for her over fifty times. She was also the model for La Bionda 1938 [52] and Jonquils and Tulips [55]. This was his final lithograph.

Curiously John Copley stopped making lithographs just as Contemporary Lithographs Ltd introduced a new generation to the medium and gave it a new lease of life. Although his early colour works were overlooked by the market at the time, they reveal a highly skilled and imaginative colourist, and their significance has come to be recognised later. He was one of the most original and prolific printmakers of his time. No other artist then working in lithography, with the exception of Nevinson, shared Copley’s ambition which he demonstrated in a series of major prints made between 1909 and 1920. The scale he chose for many his prints was exceptional and the images remained powerful when made large: Lacrosse of 1910 shows an approach to the subject and to making an image which sets it apart from the other British prints of the time and anticipates the dynamic images of the avant-garde.