Ethel Gabain has suffered from a double neglect; the almost invariable eclipse that follows an artist’s death, and the perpetual shadow of her husband, John Copley, who is always seen as the greater figure in their marriage. Perhaps this is inevitable; Copley’s work – always darker, often more harrowing – is more likely to draw the modern eye, but the comparison unfairly diminishes the work of Gabain herself, who throughout a highly productive career showed herself to be one the the foremost exponents of lithography in the England of the first part of the twentieth century.

Neither was kind to those who might wish to know more about them; indeed, their careers seem almost a model of how to avoid the public exposure necessary to assure a flow of articles and biographies to bolster a reputation. They were not much given to joining things – not the RE, the RA, few groups or alliances after the Senefelder club. They were close to relatively few other artists. Copley made lithographs when the etching boom was on, then switched to etching just as the market for them collapsed. He was a classic introvert, disdaining “Subscriptions to collective festivals or any gaudy social apparatus….”[i]Though inclined to the left, he found socialism too organised for his tastes, and described himself rather loosely as an anarchist. Gabain seems to have left even this limited engagement with the world to him, instead trying to reconcile her instincts to be a wife and mother with the creative urges that demanded she be nothing of the sort. The result was (as her son Peter described) a variety of exuberant eccentricity and cheerfulness which is, nonetheless, belied by much of her artistic output.

She was born in le Havre in 1883, half French, half Scottish and with a dash of German in her ancestry. She trained at the Slade and at the Central School of Art and Design, and by 1906 was exhibiting at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool.[ii]By then she had already turned to lithography which became her chief occupation thereafter. In 1909 she spent some time in Paris, living in the rue Boissonade in the 14th arrondissement and, when the Senefelder club was formed by Joseph Pennell and others, she was a natural member. Indeed she was probably more experienced at that stage than was her future husband, who acted as the group’s secretary. From then on, her career was one of steady progress; adopted by Colnaghi’s, she regularly had prints selected for “Fine Prints of the Year” right through the 1930’s; and with Copley held regular exhibitions in 1914, 1915, 1920 and 1921, the latter at Rouillier’s in Chicago. She was also a regular exhibitor, showing some 52 works at the Royal Academy, and 26 at various Paris salons between 1907 and 1932.

Above all, Gabain was a masterly technician, and spent years perfecting the differing methods of producing an image from a stone, becoming far more proficient than those for whom lithography was a minor sideline. She not only studied with French artists, she studied with French printers as well,[iii]and gained a proficiency which was probably superior initially to that of her husband. What she and her husband attempted was unique, not to say foolhardy: up to that point, no-one in England had been rash enough to try and make a living out of lithographs, still the most despised of the graphic arts. Few have made the attempt since. There was a price for this, literally: a lithograph by either Copley or Gabain was 3 gns in 1914, and remained the same price in 1929; in the same period a middle ranking etcher like Henry Rushbury or Francis Dodd saw their prices rise from a similar level to eight guineas and more, while etchings by the likes of Cameron or McBey changed hands for hundreds of pounds.[iv]

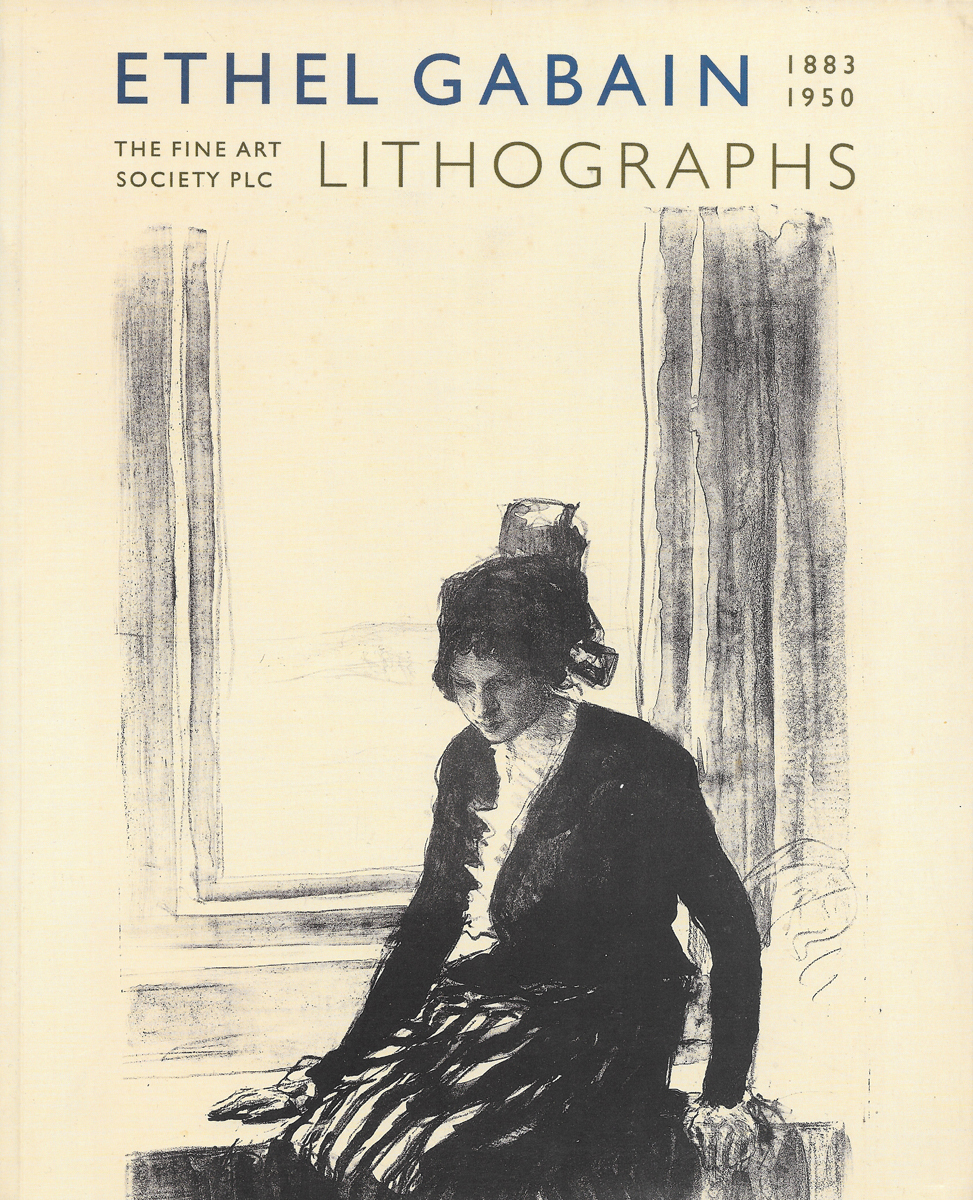

As a draughtswoman she was extraordinary, and her constant theme was that of femininity. It would be wrong, of course, to consider her a “feminist” artist; it is likely she would have snorted in derision at the very idea. Yet, in essence, that is what she was, one of the most insightful and important of her age. In image after image, she dwelt on the female condition – youth, marriage, children, work – and bought out all the ambiguities that these various states implied. In many of her works there is a sadness, an anxiety and above all a loneliness which contrasts with the often simple, even superficially sentimental, portrayals. A large number of her lithographs are of solitude, of women isolated, fearful and bored, staring into mirrors in empty rooms, sitting on the edge of a bath-tub with no-one to talk to, diminutive figures in a large and bleak space. Even a depiction of a woman on her wedding morning (1914) has nothing cheerful or optimistic about it – there is no bustle or activity around her, simply the woman herself in apprehensive solitude.

That the feminine condition itself was the abiding concern can be seen from her development in the last decade of her life. Both she and Copley changed greatly in this period, and it is one of the more remarkable aspects of their production that both managed to retain a distinctive style throughout their careers. Very often in artistic marriages, one comes to dominate and even overwhelm the other; Copley and Gabain, even though they collaborated and criticised each other, never fell into this trap. Towards the end, indeed, they began to diverge ever more notably. While Copley began to do strange, almost mystical subjects, Gabain headed in the other direction entirely.

Both of them were responding to the war and to personal ill-fortune. Gabain developed a kidney illness which required major operations in 1938, 1941 and 1943. She also became arthritic, so that in her last years she had to paint with the brush strapped to her wrist. She was philosophical about her own health: “this [operation] should give me some years, indeed as long as the kidney can be made to hold out…every day we are given is precious, years seem wealth.” (October 1938). She could not be so philosophical about the death of her son, Christopher, in early 1940. As might be expected from looking at their prints, it was Gabain who had the task of expressing the emotion; Copley’s own response was to project all his grief onto her, and to cope with his own sadness by looking after hers: “It will need time, and I think too Christopher’s help somehow from somewhere, for Ethel to be able to bear the loss. Those who can love deeply must lose hardly. She is oh so tremendously brave, but though that makes much possible it makes nothing easy….”[v]

Ultimately her response was work: while Copley retreated into a private universe of his imagination, she went outwards, missing kidney and all, reversing the pattern of World War One, when he produced many war-based images and she began a series of Pierrot pictures totally dissociated from the conflict. Copley commented on the difference in a letter to Sturge Moore: “a time of war does not help artists. Some can immerse themselves in topical matter and produce war pictures. I can’t. I need to digest things.”[vi] Within a month of her son’s death, on the other hand, Gabain was writing to the Ministry of Information offering her services for what turned out to be her last two sets of lithographs and a series of paintings.

There was a real difference in their attitude to the war itself; Gabain looked to the individual response and saw in that a subject worthy of commemoration; when asked to prepare some captions for her lithographs she wrote “I will… think out some notes on the subjects, tho’ as I went about and saw the work, I felt it was matter for an epic.”[vii]Copley, on the other hand, was more cynical about the whole effort: “Ethel is busy doing lithographs for the ministry of information. It is hard work but not uninteresting and the results are coming well; though the real artistic records of the war would be a very different thing from what is being done, and would be not at all to the ministry of information’s taste…”[viii]

She was not, perhaps, ideally suited to working for the government; indeed, being primarily a printmaker selling through galleries (principally through Harold Wright at Colnaghi’s, who had begun selling Copley’s work in 1909 and took Gabain on in December 1914[ix]) she had scarcely to deal with patrons of any sort, let alone institutional ones. Even with her dealer, she was ever hazy about the practicalities – letter after letter starts with an apology – “I am so sorry about the mistakes and about leaving the prints unsigned…”,[x]or for putting the wrong title on them, or omitting to send them at all.

Her grasp of the niceties of paperwork remained vague; petrol coupons, travelling allowances, the red sketching permits the government had decided artists needed, all bemused her, and travelling around the country in a borrowed car, carrying the heavy stones for lithographs (she preferred direct sketching and the ministry didn’t wish to pay for transferring sketches to stones) must also have been a strain on her health. Nor was she very good at remembering to ask permission in advance to visit sites; a stream of perplexed telegrams from various parts of the country had to be fielded by the Ministry, including one only six months after her third major operation

“I have had a request to arrange for flying facilities to be afforded to Mrs John Copley. It appears that this artist has been commissioned to paint certain pictures…and that she has been visiting Hendon for this purpose. How she obtained a permit to visit Hendon is nobody’s business. The medical department, now out of their depth, have passed the baby to me… You can, of course, understand that it is difficult for me to ask for facilities for her to fly, when we have not even issued her with a permit to visit… I cannot see any reason why she finds it necessary to go into the air at all. Furthermore, I understand that she is no longer young and is in ill-health… I shall be grateful if you would let me know if her desire to leave the ground is really justified. I hope the answer is no….” [xi]

Such exchanges tended to be followed by cheerfully unremorseful apologies from Gabain for causing so much trouble: “I think it was my effort to … save trouble all round, which produced the opposite result.…”[xii]she wrote after turning up unannounced at a Scottish lumber yard. Nonetheless, she persevered, her ministerial employers seemed genuinely warm towards her, and kept on producing new commissions right up to the end of the war and beyond.

By far the best prints from this period are the ones which concern women in war-time, which led her to adopt a new approach to her subject matter. Frail and sad herself, she produced a series of images celebrating robust and purposeful good health; the despondency and ennui she depicted in early portrayals had gone for good. The women are no longer isolated and enclosed; rather they are surrounded by their fellows, working together in the open air, and the pictures have a sense of light largely missing from the domestic interiors that dominated her output up to end of the 1920’s. The female lumberjacks, sand-bag fillers and pilots she drew had a place and a role for themselves, and she reflected this in a new and confident line. She did not, however, mimic the socialist-realist style of the period; her women are enjoying, not sacrificing themselves and, above all, they are still women – as she said when proposing the series:

“…it is very fine material, such lovely people — the fore lady ( they are all ladies, not women) of the sand gang is a mother of 13 and the grandmother of 9 and one of her daughters is in the gang. She wears gungarees (sic) and clogs and on the top of it all a wreath of gay artificial flowers round her cap…”[xiii]

The eye for the essentially feminine was never subsumed by the depiction of heroism; collective action never drowned out the individual. It is in this eye for the personal emotion, allied with her skill in depicting it, that her importance is to be found.

Footnotes

[i] Univ.of London Sturge Moore Ms 29/59 letter to Sturge Moore Dec 27 1940

[ii] Univ of Glasgow MS Wright c24 letter dated 19th January 1923

[iii] see Wright, PCQ 10

[iv] After the end of the etching boom, the prices fell back to pre-war levels – Dodd’s prints were quoted at 3 guineas in 1938. Prints by Arthur Briscoe were still being offered by Colnaghi at up to eight guineas, down from their peak of 12 guineas. How many were actually sold at these, or any prices, is another matter – see the various editions of Fine Prints of the Yearfrom 1924 to 1938

[v] Sturge Moore Ms 29/50 March 29 1940

[vi] Imperial War Museum Gabain Papers 2/9/42

[vii] Nov. 1 1941

[viii] July 13 1940 29/53

[ix] ms Wright c4 letter dated 4.12.14; the terms were 30 pct on sales, or 50 pct on sales to dealers.

[x] Ms Wright C8 letter dated 22.10.1916

[xi] Imperial War Museum, letter from unknown correpsondent in the air ministry, 13.1.44

[xii] Ibid July 27,1941

[xiii] Ibid 3.6.41